The Downside of Knowledge

You have probably heard the statement that education and/or acquiring more knowledge is the solution to ignorance, stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination. This article aims to challenge that thought and to explore another way of thinking about how to effectively deal with stereotypes and prejudice in ourselves and in others.

Why did I choose this tool? This topic is very close to my heart, as I have been through major paradigm shifts and changing beliefs more than once in my lifetime. Because of this I fully understand what would cause someone to hold on tightly to their beliefs even when they are wrong, what would cause a change to happen, what the process of change looks and feels like, and what amazing benefits exist on the other side of this sometimes very dark tunnel. I hope that this tool can give some insight into all of this as well as the incentive to embrace change and paradigm shifts rather than resist them.

How does this apply to being a trainer?

As trainers we are constantly dealing with knowledge, and as described in this article knowledge can and probably will change over time. It’s important not to get overconfident with the knowledge you possess, so that we don’t get too attached to the things we know because we won’t be able to recognize or accept when things have changed, or that perhaps we are wrong about something. In addition to this, during good training, the participants will undergo at least one (and perhaps multiple) paradigm shifts and/or changes in perception and/or beliefs. Knowing why they would be attached to their current ways and what it feels like to change them is essential to being able to support and motivate them in their learning process.

Main content:

It would stand to reason that increasing knowledge would support the reduction of stereotyping and prejudice, and in some cases, it can be true. If you have never met someone from a certain culture, and only formed opinions about them through the media or through second or third hand accounts, then a more in-depth knowledge about them and the nuances of their culture may contribute to letting go of the prejudices that have been formed.

However, having fixed knowledge about a culture can unfortunately also backfire, causing entire groups of people to be characterized by what is assumed to be “the norm” in that culture, not allowing them to show their unique selves and how they implement or don’t implement, their countries’ culture.

Here it is also valid to make the distinction between knowledge and wisdom, and this distinction is very important when it comes to intercultural awareness.

The google dictionary defines knowledge as:

“Knowledge is facts, information, and skills acquired through experience or education; the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject.”

While Wikipedia defines wisdom as:

“Wisdom is the ability to think and act using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense and insight. Wisdom is associated with attributes such as unbiased judgment, compassion, experiential self-knowledge, self-transcendence and non-attachment, and virtues such as ethics and benevolence.”

Clearly, wisdom involves a lot more than acquiring facts, and interacting with another culture certainly requires a high level of wisdom rather than just knowledge. Knowing the facts without having the wisdom of how to use that information can actually lead to stereotyping and prejudice.

The potential link between knowledge, stereotypes and prejudice

Whatever we know, we assume is true

Whatever knowledge we acquire and accept, in this case regarding another culture or group of people, we will assume is true unless it is otherwise proven (and even then we will have a tendency to stubbornly hold onto our existing beliefs). The reason for this is that our brains are wired to want certainty, to want to be right, and to provide us with a clear direction and solid decision-making abilities. Questioning everything we know all the time would be exhausting, would take a lot of time, and would keep us in a constant state of limbo never knowing what direction to go in, what to do or not do, who to trust, and what to believe. We need our certainties, and we need are facts. Even if those facts aren’t as factual as we believe they are.

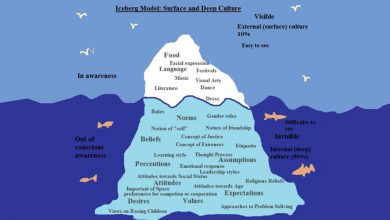

What we know, what we don’t know that we know, what we don’t know, and what we don’t know we don’t know .

There are things we know, there are things we know that we don’t know, and there are things that we don’t know that we don’t know.

What we know

There are things we know, for example that the sky is blue today. Although there could be different ways of expressing blue (mavi, الازرق, bleu) the sky being blue is something we can consider a solid fact for the moment in time in which it is, in fact, blue.

What we don’t know that we know

There are times when we are certain that we don’t know something, but when we get into it a bit we start to understand that we know a lot more than we originally thought that we did. We can consider this a type of prejudice against ourselves. To give an example, when I gave my very first real training, I didn’t mention this to the participants in the beginning. I just delivered the training with my team as if we all knew exactly what we were doing. At the end of the training, after we received so many positive evaluations, I mentioned to one or two people that it was actually my first real training. They were shocked and surprised and said that it seemed like we had been doing this for years. It was then that I realized that even though I hadn’t done it before, I knew how to deliver the training probably due to an accumulation of knowledge and skills that I had acquired in other ways.

What we don’t know

There are things that we know and accept that we don’t know, and this of course will vary from person to person. I for instance don’t know how to drive. I know that I don’t know how to drive, and therefore I don’t get into a car and try to drive, risking injury or death. Another example would be the case of someone who knows that they don’t know how to speak French. Knowing that they don’t know how to speak French would probably keep them from trying to engage in a deep conversation in French, since they know, it would be a futile and silly attempt.

What we don’t know we don’t know, or think that we know

Here is where we as humans really have a problem, and it’s a problem that can lead to many other problems if we allow it to. So I know how to distinguish different colours and to say what colour the sky is at the moment, I discovered that I actually know how to deliver a training, and I know that I don’t know how to drive so I don’t try (at least not without someone who knows).

However what if I don’t know that I am not aware of how to comfort someone who was sad, and I was suddenly faced with this situation. Would I be utterly perplexed by it? Or if I thought I knew that women in certain countries were always oppressed, and turned out to be very wrong? Or if I thought that eating fatty foods made you fat and unhealthy, and then I discovered that eating the right kind of fats can actually make you lose weight and be even healthier?

We all have things that we think we know that turn out to be wrong or things that we simply don’t know we don’t know. There is no way to know everything or even to be able to list everything that we don’t know. The world would be a bit boring in that case, with no surprises or challenges (or at least no surprise challenges).

What makes a difference between someone who is prone to dogmatism, stereotyping and prejudice and someone who is open-minded and ready to learn something new is not how much they know, or even how much they know that they don’t know. It’s about how they react when something that they believe to be true is challenged by new facts, or by seeing or experiencing something that doesn’t fit with their current belief. Do they reject it and hold onto their existing beliefs and knowledge even more tightly? Or do they actually seek out opinions and experiences that challenge their existing paradigm, and thereby open themselves to being “wrong” for the sake of finding the truth, how painful that might be?

It isn’t natural to be changing our paradigms, beliefs and habits all the time. That’s why it is much more common for people to decide who they are, what they do and where they live, what they think about other people and different cultures, and stick to that, possibly for the rest of their lives. It’s what our brains and bodies are wired for, finding something that works and sticking with it. It usually takes a crisis or some major event for someone to even consider the possibility of major change, and even then they can still ferociously resist changes to their deeply ingrained beliefs and mindsets, even if they know that their lives could be better if they changed them.

On the flip side, you will occasionally encounter someone who doesn’t really stick to anything, whether it’s a belief, a mindset, a habit, a job, a country, a relationship, or anything else. They may tell you that they embrace everything, love everyone, and live life by going with the flow. Although this may be nice to experience for a while, especially when experiencing a time of shifts, transitions and change, staying this way may not be sustainable for the long term, particularly if one wants to build something solid and experience the joys of achieving long term results.

There is a third way, that doesn’t require going to either of these extremes. I call it “living an examined life” based on the quote from Socrates that “an unexamined life is not worth living”.

Living an examined life means that you have your beliefs, your chosen lifestyle, your habits, your profession or job, your way of eating, your knowledge bank that you have acquired over the years, your beliefs and opinions about other people and cultures, your hobbies and entertainment preferences, your way of thinking about yourself and other people and cultures. But you are not on autopilot, at least not always.

You have critically examined, or are willing to critically examine, everything about yourself, the knowledge you have, and especially your beliefs and mindsets. You know that you are capable of change and paradigm shifts, because you have already gone through a few in your lifetime.

When you are faced with a fact, event or person that challenges your existing beliefs and/or modus operandi, you don’t dismiss it offhand. You take it into serious consideration, and you question whether or not it might be true, or also true. You accept that you may have been wrong about something or someone, or that you may be right but that another seemingly contradictory truth may also exist alongside it. You reject black and white thinking, while at the same time you have an established moral code for yourself that you stick with no matter what (unless you are presented with information that would warrant updating or changing it).

Living an examined life is not easy. It takes courage and a whole lot of mental energy to question ourselves, our beliefs, the status quo and the accepted norms. But the alternative of living on autopilot and accepting everything as it seems to be lead to not only unquestioned stereotypes and prejudices but also to potentially bad decisions and not being the best version of yourself that you can possibly be.

Here are some tips on how to realistically live an examined life:

- Don’t try to do it all at once.

Choose an aspect of your life that’s a priority right now, and examine that. Then when you’re settled for now in that aspect, you can tackle another one.

2. Do it carefully.

When you’re faced with something that challenges your existing paradigm, don’t change everything immediately. Consider it carefully, and get more information particularly from unrelated sources that have no stake in the matter. Piece all the information together, draw your conclusions, and then change if you deem it necessary.

3. Be more attached to the truth than being right.

This is one of the main reasons why a lot of people resist change. They are more attached to being right than to know the truth.

4. Give yourself a break

When we are faced with new and potentially life-changing information, it’s natural to feel bad that you have been “doing it wrong” or “thinking about it wrong” all this time. This is especially true if how you were doing things or thinking before has hurt you or someone else. Keep reminding yourself of this fact: You can’t judge you from the past based on what you know today. Be grateful for what you know now, and move forward in a better way then you did before.

5. Be infinitely curious and ask questions

There is so much still to discover, particularly when we are talking about other people and other cultures. Instead of seeing it as a chore to get new information or insight about another culture, see it as an interesting game that you can get better and better at. When you don’t understand something, have enough genuine curiosity and concern to just ask and get your info directly from the source (instead of second or third hand from the media or unrelated people eager to share their opinions).

6. Test what you know

Whether it’s old knowledge or newly acquired knowledge, test everything you know instead of taking it for granted. Do it with an open mind and keep your biases in check so they interfere as little as possible with the process. If someone tells you that computer games lead to violence, try playing them for a while and see whether or not you feel more violent as a result. If you learn that Italian food makes you fat, try eating it for a week and see if you have any change in your weight. If you hear that Muslims, Christians or Jews are dogmatic and mean to others not from the same religion, talk to one (or a few) and see how it goes. Test it yourself, and talk to other people who have been doing it as well. How do they feel? What results do they get? Thankfully we now live in a world where everything is possible, so the only way to find your way and to live a truly examined life is to actually experiment as much as you can with as much variety as you can before taking a solid stance one way or another.

7. Accept the challenge of being a lifelong learner

When we learn something new, we tend to get a certain amount of information and then be done with it, comfortable that we are now experts on the matter and don’t need to go deeper with it. With this mind-set, being exposed to something new on the matter can overwhelm us. “And here I thought I was done with that!” Although we may change our focus on what we are learning about, we must accept that knowledge can and will change, and we have to be open to updating and revising accordingly. What was commonly accepted as truth 100 years ago, or even 10 years ago, is radically different from what is commonly accepted as truth today; in some cases it is even the opposite. Naturally, this means that in 10 or 100 years, things will be radically different from how they are today. The sooner we accept all of this, the sooner we can relax and start enjoying the process of learning and change rather than desperately trying to stay set in our ways.

Closing:

“In a world of change, the learners shall inherit the earth, while the learned shall find themselves perfectly equipped for a world that no longer exists.”

Reflection questions:

What was something you were completely sure about, that turned out to not be true?

How did you feel when you discovered that it wasn’t true?

Would you rather have continued to believe that it was true, or were you happy to have found out the truth?

What insight does that give you about yourself?

Exercises

1. Be more attached to the truth than being right

2. Be infinitely curious and ask a lot of questions

3. Test what you know to see if it is true (and test it again to see if it’s still true)

4. Cheerfully accept the challenge of being a lifelong learner