Hofstede’s cultural dimensions

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are often used when addressing the topic of culture and interactions between cultures. It is also rather controversial to put entire countries into certain categories and to expect the same values and behaviors from all the individuals who are from that country. This article offers an overview of Hofstede’s model of cultural dimensions, but also suggests an approach of how it can be applied without leading to unnecessary stereotypes and assumptions.

Why did I choose this tool? Because Hofstede’s work is considered to be so important in the field of culture and intercultural studies, I felt it should be included in the intercultural competence. However, I also look at it critically and can think of situations where this model could be very helpful, as well as situations where it wouldn’t be helpful at all. I hope that you will also read it critically and come to your own conclusions about it.

How does this apply to being a trainer? The main way I can see this being useful to us as trainers is to take it into consideration when we are faced with participants (or even fellow trainers) that have a different framework than our own and operate differently. I believe that understanding this framework will help us to avoid categorizing behaviors into “good” and “bad”, “right” and “wrong”, but rather to understand it as “my framework” vs. “your framework”. In this way we can avoid judgment and instead work on understanding what framework differences may be causing the conflict, and how we can productively address them.

Main content:

Professor Geert Hofstede conducted one of the most comprehensive studies of how values in the workplace are influenced by culture. He defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from others”.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory is a framework for cross-cultural communication. It describes the effects of a society’s culture on the values of its members, and how these values relate to behavior, using a structure derived from factor analysis.

Hofstede developed his original model as a result of using factor analysis to examine the results of a worldwide survey of employee values by IBM between 1967 and 1973. It has since been refined to include additional elements.

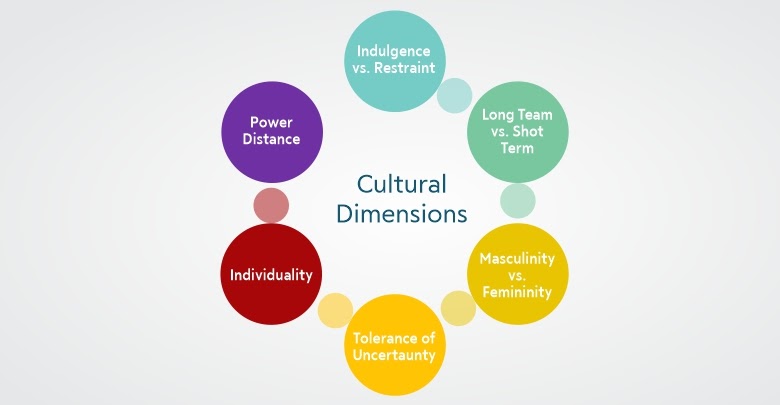

The current Hofstede model of national culture consists of six dimensions. The cultural dimensions represent independent preferences for one state of affairs over another that distinguish countries (rather than individuals) from each other.

The country scores on the dimensions are relative, in that we are all human and simultaneously we are all unique. In other words, culture can only be used meaningfully by comparison. The model consists of the following dimensions:

Power Distance Index (PDI)

This dimension expresses the degree to which the less powerful members of a society accept and expect that power is distributed unequally. The fundamental issue here is how a society handles inequalities among people.

People in societies exhibiting a large degree of Power Distance accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and which needs no further justification. In societies with low Power Distance, people strive to equalize the distribution of power and demand justification for inequalities of power.

Individualism versus Collectivism (IDV)

The high side of this dimension, called Individualism, can be defined as a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of only themselves and their immediate families.

Its opposite, Collectivism, represents a preference for a tightly-knit framework in society in which individuals can expect their relatives or members of a particular ingroup to look after them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. A society’s position on this dimension is reflected in whether people’s self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “we.”

Masculinity versus Femininity (MAS)

The Masculinity side of this dimension represents a preference in society for achievement, heroism, assertiveness, and material rewards for success. Society at large is more competitive. Its opposite, Femininity, stands for a preference for cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life. Society at large is more consensus-oriented.

In the business context, Masculinity versus Femininity is sometimes also related to as “tough versus tender” cultures.

Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI)

The Uncertainty Avoidance dimension expresses the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact that the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen?

Countries exhibiting strong UAI maintain rigid codes of belief and behavior, and are intolerant of unorthodox behavior and ideas. Weak UAI societies maintain a more relaxed attitude in which practice counts more than principles.

Long Term Orientation versus Short Term Normative Orientation (LTO)

Every society has to maintain some links with its own past while dealing with the challenges of the present and the future. Societies prioritize these two existential goals differently.

Societies who score low on this dimension, for example, prefer to maintain time-honored traditions and norms while viewing societal change with suspicion.

Those with a culture which scores high, on the other hand, take a more pragmatic approach: they encourage thrift and efforts in modern education as a way to prepare for the future.

Indulgence vs. Restraint (IND)

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it through strict social norms.

How we can apply this model

Although Hofstede’s model includes classification of more than 70 countries according to the above-mentioned dimensions, I haven’t included them here because I believe that categorizing countries according to these dimensions can lead to stereotypes and automatic assumptions about people, which can actually prevent the development of Cultural Intelligence.

However, I do believe that understanding these potential differences in perception can lead to understanding and minimizing conflict between people with different value systems, particularly if we understand that there is no “right perception” or “wrong perception”, merely different perceptions.

We can find positive or negative results in either aspect of each dimension. Taking for instance the “individualism or collectivism” dimension. Individualism could be very positive in a young person who is studying and working hard to create a life for themselves, rather than sitting back and relying on their family’s wealth to support them no matter what they do or don’t do. Collectivism, on the other hand, can be extremely beneficial when a country suffers from a natural disaster (like an earthquake) and members of the society are quickly mobilized to help those in need without waiting for those with the official responsibility (such as the government) to be the only ones to take action.

It is so easy to get trapped in our own framework of what is right and wrong and look down on those who don’t behave according to that framework and even try to change them so that they can fit better into our own framework. By understanding that they have their framework and that they are acting in the way that they feel is correct according to the framework that they hold, it becomes easier to empathize, understand and even possibly adapt to their way rather than expecting them to adapt to ours.

It is also interesting to note that in spite of the different frameworks and values that exist between cultures, some values are universal to every culture. The book “Culturally Intelligent Leadership” states that they uncovered the following universally desirable and universally undesirable characteristics for leadership.

Six global positive leadership characteristics emerged from the GLOBE data: charismatic, team-oriented, participative, humane-oriented, autonomous, and self-protective.

The GLOBE data points to universally positive and undesirable attributes of leaders. All cultures agree that the following are negative attributes: a leader who is a loner, irritable, ruthless, asocial, nonexplicit, dictatorial, noncooperative, and egocentric.

This shows that regardless of what your cultural orientation is, there are some attributes that you can develop that will be universally appreciated regardless of the cultural context you find yourself in.

Cultural frameworks and acceptable behavior are learned based on the type of culture one is raised in. Cultural frameworks are not inherent, and therefore they can change. A baby is not born with a concept of power distance and whether it is acceptable or not. They learn this later on based on the behavior of their caregivers and the society they grow up in. Emotions, on the other hand, are inherent and universal. And how, you might ask, are emotions and cultural frameworks related?

The cultural framework can be seen as the learned code which triggers a certain emotion. For instance, someone who is raised to believe that uncertainty is negative and should be avoided at all costs will feel fear and anxiety automatically when faced with uncertainty. Perhaps you have been raised to believe that uncertainty is a natural part of life and not to be feared, so you may not understand the strong uncertainty avoidance that is driving your colleague. However, you could understand and empathize with the emotion that is being triggered by the uncertainty, fear and anxiety, because they are universal. For you however, it isn’t triggered by uncertainty but rather by walking alone at night in a neighborhood that is considered to be dangerous. So, although you can’t relate to the cultural framework, you can still empathize with the individual and the emotions they are experiencing, because you as a human being are capable of feeling the same way.

The cultural framework can simply help us to understand how someone might be feeling, and why they might be feeling that way. As a trainer, it can help us to adjust our approach if we see that the framework we are operating in is provoking a negative reaction. For instance, if we are giving a lot of individual tasks to participants, perhaps a participant who is more used to a collectivist culture will feel a bit lost and prefer to work in a group rather than alone. Understanding this may lead you to balance the activities better so that the different frameworks are taken into consideration and addressed.

In short, I believe that Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions model can be helpful when used as a guide for understanding different cultural frameworks and values, rather than a tool to categorize and label countries and individuals.

Reflection questions:

Where do I stand on each of these dimensions?

Power Distance Index

Individualism versus Collectivism

Masculinity versus Femininity

Uncertainty Avoidance

Long Term Orientation versus Short Term Normative Orientation

Indulgence vs. Restraint

Is my stance based on my cultural upbringing or the decisions that I made?

Do I tend to clash with people who are on the opposite side of the spectrum?

If so, does this article help me to understand their value system better?

Could there be some instances where the perspective of those on the opposite side of the spectrum are more useful than mine?

What aspects of my personal culture would I like to adapt to or change?

Exercise:

When you are interacting with people from different cultures, look for the above mentioned traits. Remember that your goal is not to stereoptype but to understand. Do you see signs of uncertainty avoidance, or individualism vs. collectivism? Think about how you can be more effective in communicating, working and collaborating with people who are on the opposite side of the scale as you are.